William Faulkner

William Faulkner: The Immortal Man

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1949

William Faulkner's speech at the Nobel Banquet at the City Hall in Stockholm,December 10, 1950

Ladies and gentlemen,

I feel that this award was not made to me as a man, but to my work – a life’s work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before. So this award is only mine in trust. It will not be difficult to find a dedication for the money part of it commensurate with the purpose and significance of its origin. But I would like to do the same with the acclaim too, by using this moment as a pinnacle from which I might be listened to by the young men and women already dedicated to the same anguish and travail, among whom is already that one who will some day stand here where I am standing.

Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.

He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed – love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, of victories without hope and, worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.

Until he relearns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last dingdong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking.

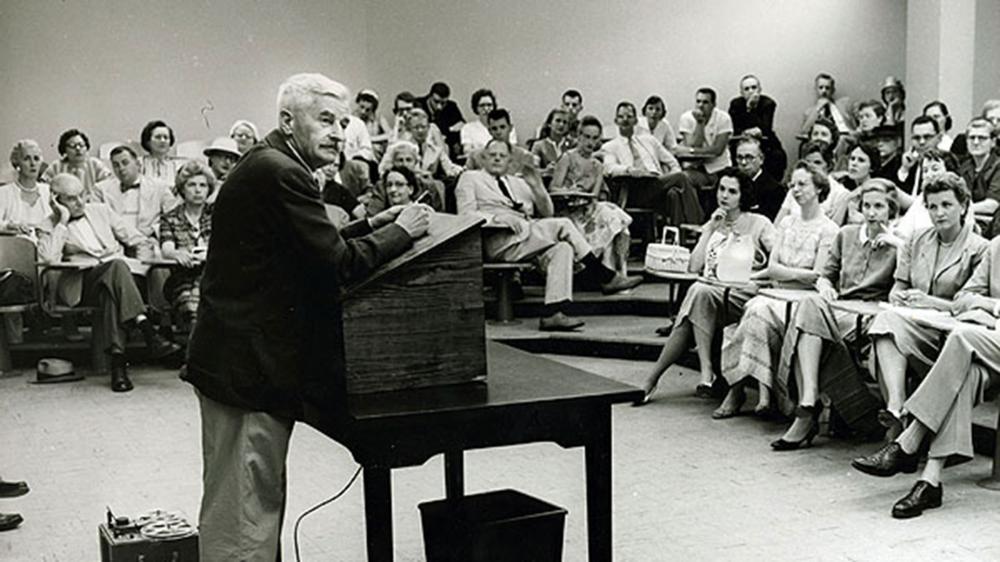

William Faulkner at Rouss Hall in 1957

I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.

From Nobel Lectures, Literature 1901-1967, Editor Horst Frenz, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1969

Review & Assess

1 Respond: Do you agree with Faulkner’s definition of good literature?

If not, how would you revise it?

2. [a] Recall: According to Faulkner, why are there no longer problems of spirit?

[b] Deduce: What is the physical fear to which he refers?

3. [a] Recall: According to Faulkner,what alone is the subject matter of good writing?

[b] Interpret: Why does he view most modern literature as ephemeral?

4. [a] Recall: According to Faulkner, will humanity endure or prevail?

[b] Define: In what way does Faulkner define the difference between enduring and prevailing?

5. [a] Recall:According to Faulkner, what is a writer’s “duty”?

[b] Interpret: What distinction does he draw about ‘the poet’s voice” in his explanation of how humanity can prevail?

6. [a] Extend; What events not long before 1950 gave rise to the fear of which Faulkner

speaks?

[b] Hypothesize: If he were alive today, would he say we have lost or retained that fear?

Explain.

William Cuthbert Faulkner (September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer and Nobel Prize laureate from Oxford, Mississippi. Faulkner wrote novels, short stories, a play, poetry, essays, and screenplays. He is primarily known for his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, based on Lafayette County, Mississippi, where he spent most of his life.

William Faulkner’s writing

Faulkner was known for his experimental style with meticulous attention to diction and cadence. In contrast to the minimalist understatement of his contemporary Ernest Hemingway, Faulkner made frequent use of “stream of consciousness” in his writing, and wrote often highly emotional, subtle, cerebral, complex, and sometimes Gothic or grotesque stories of a wide variety of characters including former slaves or descendants of slaves, poor white, agrarian, or working-class Southerners, and Southern aristocrats.

In an interview with The Paris Review in 1956, Faulkner remarked:

Let the writer take up surgery or bricklaying if he is interested in technique. There is no mechanical way to get the writing done, no shortcut. The young writer would be a fool to follow a theory. Teach yourself by your own mistakes; people learn only by error. The good artist believes that nobody is good enough to give him advice. He has supreme vanity. No matter how much he admires the old writer, he wants to beat him.

Another esteemed Southern writer, Flannery O’Connor, stated that “the presence alone of Faulkner in our midst makes a great difference in what the writer can and cannot permit himself to do. Nobody wants his mule and wagon stalled on the same track the Dixie Limited is roaring down”.

Faulkner wrote two volumes of poetry which were published in small printings, The Marble Faun (1924) and A Green Bough (1933), and a collection of crime-fiction short stories, Knight’s Gambit (1949).

Faulkner’s work has been examined by many critics from a wide variety of critical perspectives. The New Critics became very interested in Faulkner’s work, with Cleanth Brooks writing The Yoknapatawpha Country and Michael Millgate writing The Achievement of William Faulkner. Since then, critics have looked at Faulkner’s work using other approaches, such as feminist and psychoanalytic methods.Faulkner’s works have been placed within the literary traditions of modernism and the Southern Renaissance.

Tuition in English Literature Cambridge, EDEXCEL & National at Kandana by bunpeiris

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TUITION KANDANA bunpeiris