The Divorcee and The Defeated

“The Divorcee” and “The Defeated”: the socially condemned

“Both Ken Saro-Wiwa and Nadine Gordimer portray the plight of groups of people who have been socially condemned.”

Discuss this statement with reference to short stories ‘The Divorcee” and ‘The Defeated.”

Written in PEEL [Point, Explanation, Evidence, Link] format by BunPeiris

Both Ken Saro-Wiwa and Nadine Gordimer portray the plight of groups of people who have been socially condemned. In his “Divorcee,” Saro-Wiwa portrays the plight of gender-based social inequality inherent in a tribal society that survives in the margins of the socio-economic system of Ogniland of Nigeria. In the same vein, in her “The Defeated,” Nadine Gordimer poRtrays Jewish immigrants that were subjected to social inequality and the native Africans that were subjected to constitutionalized racial segregation during Apartheid laws of South Africa. But then Gordimer goes further: she depicts the social class system within a socially condemned community itself that seeps into the relationships among the ageing parents and their adult children in their prime.

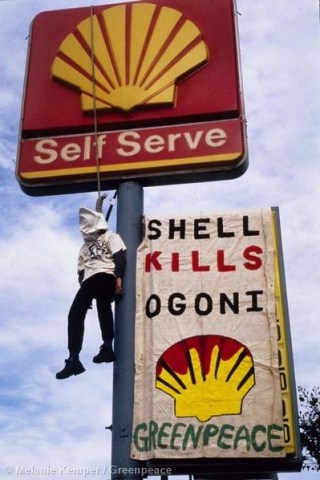

Ken Saro-Wiwa (1941-1995), who single-handedly mobilised his Ogoni people from state of political suffocation to a state of political consciousness and environmental alertness in the backdrop of the degradation of land and waters of Ogoniland caused by the oil drilling operations of the multinational petroleum industry, especially the Royal Dutch Shell company, was primarily a Nigerian writer activist, amidst an array of other occupations and vocations. His execution by the oppressive Nigerian regime fanned the fires of international outrage that resulted in suspension of Nigeria in the commonwealth for over three years. Saro-Wiwa was a voice that rose up against the suppression of his countrymen suffering at the hands of ruling regimes. He lived and died a hero. His legacy is bound to echo throughout the world wherever and whenever the suppressed classes are endlessly strangled by the oppressive regimes: “……it being my credo that literature in a critical situation such as Nigeria’s cannot be divorced from politics. Indeed, literature must serve society by steeping itself in politics, by intervention, and writers must not merely write to amuse or to take a bemused, critical look at society. They must an interventionist role.” (Okome)

He reveals to the world, a winter of discontent ingrained within the socio-cultural-political system of Nigerian life: inefficiency; waste; bribery; corruption and at last but not least, ostentatious living of those in power. Over and above those crimes and sins were the tribal chauvinism underpinned by peculiar norms and mores. Among those is an unfair provision for divorce: “childlessness: among the Ogoni there is a deep conviction that children are a blessing. Therefore, lack of children is considered a misfortune, or a sign of a curse. They believed a marriage without children has not yet achieved its objectives. As Okunola (2002) expressed, procreation takes priority in marriage for an African man because a child is considered instrumental to establishing a lasting family (Osiki, 2000; Salami & Bakare, 2001).” (Christian Radu CHEREJI)

However, there was no ruling for a requirement of the determination of the source of barrenness in marriage. As result, the fault was thrown upon the weaker gender, the wife. The ruling is generally enforced: yet, neither husband nor wife is required to be clinically tested in terms of fertility. Herein is the situation, the women are subjected to social inequality. Herein is the context, where the weaker gender is socially condemned.

In his short story “Divorcee,” Saro-Wiwa brings the bitter side of a victim of divorce rulings to the limelight. The plot begins with In medias res, (Latin: in the midst of things): “Lebia walked the sandy pathways of Dukana early every morning, a loose piece of cloth draped round her shoulders, an earthen pot finely balanced on her head.” She is already divorced but young and lissome: “Her neck was long and elegant and her legs straight as a palm.” She is young, yet already devoid of cheer: “She walked alone. At a fast steady pace, unsmiling, and looking neither left nor right.” Lebia is returned to her mother’s hut early one morning, following three years of marriage, by her husband. Her offence: she has failed to bear children. Without the source of barrenness being clinically determined, the entire blame has been thrown upon her. Then the narrative runs ahead: exposition of earlier events during the three years of marriage is supplied by flashbacks. She is a lissome young woman of matchless grace that toils day in, day out, without a single word of discontent: “She cooked his meals, washed his clothes and swept their one room apartment. And at night, when he had had his meal and his bath, she did her duty. Faithfully. Loyally. Every day.” As Jane Austen puts it in her Pride And Prejudice, marriage is often woman’s “pleasantest preservative from want.” In Dukana, not unlike the world over, and especially the third world over, the economic necessity defines the prime want and “ultimate aim” of a Dukana woman: marriage. Dukana social fabric is such, a woman could be “the only wife of a poor man or one of the many wives of a rich man.” But then Lebia’s security of marriage is not destined to last long; the shame of being divorced by her husband is to last for the rest, the longer phase of her life. Her husband, “expected she would bear children …If he did not become a father, there was something wrong with his wife.” And it is taken granted that nothing is wrong with the man. Only the female could be responsible. The punishment is divorce. The bride’s parents are forced to return bride price. It is in such circumstances, Lebia is returned to her mother and the divorced man has his bride price returned to him. The smaller fish is eaten by the small fish. The suppressed is suppressed by the one less suppressed. Herein is the plight of socially condemned weaker gender in Dukana.

As she has lived throughout the three years, even at the situation, wherein her husband tells her to get all her clothes packed, Lebia has no voice: she utters no words. As she has lived all those three years at the beck and call of her husband, she would still obey his command to return home to her mother. Such is the situation of the socially condemned weaker gender in the tribal community of Dukana, she would not consider, it is her place to do anything else other than what she is told by her husband. Social inequality inflicted upon the feminine gender cannot get any worse. Such is the plight of weaker gender in Dukana: socially condemned. Condemned to silence in ending the marriage.So was in the beginning her marriage too. Even when her uncle asked her whether she would like to marry the young driver: “shy as she was expected to be, she refused to say a word.”

But then, her situation in terms of very existence could have become worse, had not her mother still lived; “She was lucky [her home] was still there in it, and her mother in it, alive and well.” Had not her mother lived, she could have been thrown to the street by her husband. Such a possibility can be seen in the backdrop of her husband’s violence at home. That her husband had been such, she, “would have given the world to forget,” nothing else but, “the nightmare of those three years [of] brutality,” in marriage. It is in this manner that Saro-Wiwa reveals the spillover of the gender-based social inequality ingrained in the tribal custom related to Aaba [divorce] of Dukana: the weaker gender is socially condemned.The narrative tone is basically dispassionate. Yet it is a heart-rending example for the plight of groups of people who have been socially condemned.

In the same spirit Ken Saro-Wiwa is the writer activist martyr of the Nigerians who suffered under a succession of oppressive regimes, Nadine Gordimer [1923-2014] is the writer activist demi-goddess of the black, brown and coloured masses of South Africa who suffered under the Caucasian White South Africans’ [Afrikaans speaking descendants of the Dutch East India Company’s original settlers, known as Afrikaners, and the Anglophone descendants] constitutionalized Apartheid segregation of races. A champion of free speech and tolerance, Gordimer refused to become an exile, even though three of her books were banned. She would not confine her activism to an onslaught against Apartheid. Gordimer refused to be complacent in the face of state censorship and control of information.

Gordimer’s “The Defeated” unfolds with the introduction of two social classes: the narrator’s mother has discouraged her from roaming round the area of the concession stores since they, “smelled, and were dirty and the natives spat tuberculosis into the dust,” But then, her mother, deemed it unnecessary to educate her child, that the cause of tuberculosis is their own mine wherein native [negroid] South Africans, of lowest level of South African segregation, are hired. The narrator too fails to view her own family prosperity would not have existed if not for the native African mineworkers, in spite of their labour day in and day out, are already defeated in their struggle raise the quality of life. The underclass is exploited by the highest class to such an extent, even amidst the spread of tuberculosis, medical facilities have not been extended to the miners. Herein Gordimer reveals the plight of groups of people who have been socially condemned.

In spite of her mother’s warning, the narrator drawn in by the “signs of life,” begins to “wander down,” the roads. It was in such an occasion that she comes across her classmate Miriam Saiyetovits, the daughter of a Jewish immigrant family. The narrator smiles at Miriam, “very friendly.” But then, that was only following some moments spent in staring at each other. Miriam unaccustomed to those in the social class higher to her, hesitate to react, catching the moment. Their difference in social classes is such they had to decide “to recognize one another” to make a move: “she sauntered over to talk to me.” The social class difference between them is such, they seems not to have been friendly at school, though both of them have been in same graded class. Following their interaction, the narrator confesses that their, “relationship at school continued unchanged, just as before.” That is to say they behaved as they have not met each other at Miriam’s home and made friends with each other. The narrator as well as Miriam has moved strictly with their own social classes even in the school: “she had her friends and I had mine.” Their friendship is compartmentalized to the world outside of the school: “…but outside of school there was the curious plane of intimacy on which we had, as it were, surprised one another.” Therein is revealed that outside of the school, they behave as if there is no existence of social class system at all. Their circumspection with respect of their friendship is such, they seems to avoid disturbing the entrenched social class system. Although both segments of populations are Caucasian Whites, such was the gap between the well-educated English speaking White South Africans and merchant Jewish immigrants whose command of spoken English language is minimal and written language is nil. Herein Gordimer reveals the plight of Jewish immigrants who are socially marginalized, if not condemned outright.

Saiyetoitzes not unlike the native South Africans, in spite of owning a concession store, a sort of department store, are occupied in “hard work, dirty work with the sweet, sickly body-smell of the black men about him all day.” They strive to make their way to higher social class: “Ve’ll be in d’house, and everything’ll be nice, just like you want.” But they appear to be defeated in their struggle raise the quality of life: “Saiyetovitz made no money, only worked hard and long, standing in his damp shirt amidst the clamor of the stores.” While the rest of the shopkeepers become affluent, Saiyetoitzes, the immigrants hampered by the lack of local “instinctive peasant craftiness,” are occupied with sheer hard work. Although they have a new house build in the township nearby, they need to stay at the compartment behind the concession store so that trading could be run. In spite of being witnesses to the poverty and misery of the native Africans working hard to rise above the poverty, Saiyetoitzes are not bothered in sparing a sympathetic glance particulary at them. Mr. Saiyetoitz, running his business at the concession store, “treated the natives honestly but with a bad grace.” He is content in leaving them to feel their “ignorance, their inadequacy.” In the same way the class higher kept their distance from him, in the same way he was left to feel submissive to the higher social class, he left the native Africans sink in their own inferiority. The small fish eats the smaller fish. The one less suppressed suppresses the one further suppressed. Herein is the plight of socially marginalized, if not condemned Jewish immigrants to South Africa.

Miriam sees all, observes all yet seems to be indifferent to all matters, all issues surrounding her, to wealth as well to poverty. The narrator seems to be taken aback that Miriam refuses to make a comment here and there, throw an admiring glance now and then in the airy, pretty, bright, well-furnished home of hers, “full of flowers and personal touch of [her] mother.” Miriam did nothing of an admiring, gracious guest but, “all afternoon she looked indifferently as she did at home.” It could either she was weary of praising luxury or simply thought that she could, in future, rise above her social class, and live a stylish luxurious life. Gordimer would have no hand in uncovering Miriam’s thoughts. Gordimer simply leaves, to the readers, observations sans judgments. Though every child would value his parents, no matter how humble, above all the rest of the people, Miriam is at variance even in aspect too. In one point of time, Miriam declared her preference for narrator’s father over her own father: “…if you had to choose somebody, a certain kind of person for a, well, your father’d be just the kind you’d want. That was while travelling to town for Miriam to buy a “new winter coat which she had wanted very badly and talked about

longingly for days, and her father had just given her money to get it.” Irony. Herein is revealed, in spite of all her pretentions of indifference, Miriam’s sense of inadequacy. Herein is revealed the plight of socially marginalized, if not condemned Jewish immigrants to South Africa socially, albeit strictly in terms of social standings.

The narrator loses the close relationship with Mariam when each of them secure employment in their fields. The narrator on the very first instance that she returns home on vacation from her employment visits Mariam’s parents at the concession stores. Miriam has distanced herself from her home, from her parents: “They had seen Miriam’s little boy only three times since he was born. They had seen Miriam, “hardly at all; her husband never.” Moreover, she has failed to invite her parents to her home.” Such were the facts sans opinions. Mariam’s mother would not vent her grief. Mariam’s father, having resigned to his fate of being deserted by his only child, would not be judgmental, but only disappointed: “it does not come out like you think,” he said. Saiyetoitzes had been defeated in their struggle to raise the quality of life and rise above their social class during Miriam’s upbringing and higher education. Then again, during their daughter’s employment and married life too, they have been defeated once again. Herein Gordimer reveals the plight of socially marginalized, if not socially condemned Jewish immigrants to South Africa.

Ken Saro Wiwa and Nadine Gordimer are not merely writers who have taken up their art merely for the sake of art. As Saro-Wiwa once put it, the aim was to, “create an awareness of [their, i.e. Nigerians] predicament. This was the most important thing. We are in the trouble as a nation. And unless people realize this, they would not be able to change their habits.” (Okome 181)Gordimer too aired her views in a similar breeze: ” The tension between standing apart, and being fully involved; that is what makes a writer.” (Feder) 161 Both were at once, activists and writers. While Saro-Wiwa portrays the plight of Nigerian woman who suffer as a result of gender-based social inequality, Nadine Gordimer portrays the plight of community of Jewish Immigrants to South Africa that was subjected to social inequality and native Africans subjected to constitutionalized racial segregation. But then Gordimer goes further: she depicts the spillover of social inequality into the very relationships among the toiling and aging parents and their sons and daughters, in their prime, who rose above their social standings during childhood, adolescent and university age. End. Written by BunPeiris.

Works Cited

Christian Radu CHEREJI, Charles WRATTO KING. “ASPECTS OF TRADITIONAL CONFLICT MANAGEMENT PRACTICES AMONG THE OGONI.” Conϐlict Studies Quarterly, Issue 10, (January 2015, ): pp. 56-68.

Feder, Lillian. Naipaul’s Truth: The Making of a Writer. Maryland, U.S.A: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2000.

Okome, Onookome. Before I Am Hanged: Ken Saro-Wiwa, Literature, Politics, and Dissent . Trenton, NJ 08638: Africa World Pr , 1999.