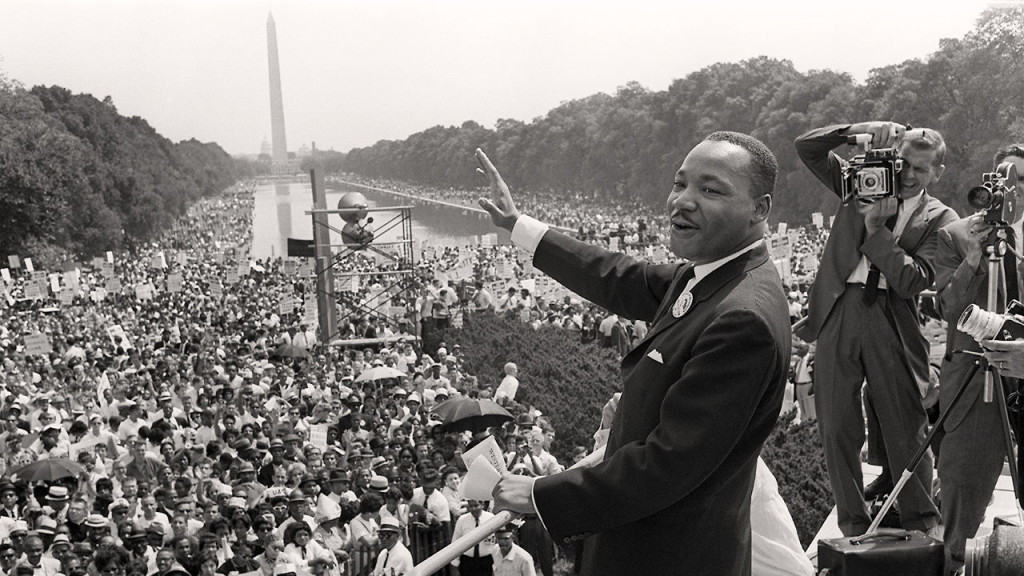

Reading an essay to an audience can bore them to tears. I recently attended a conference where a brilliant man was speaking on a topic about which he was one of the world’s experts. Unfortunately, what he delivered was not a speech but an essay. This renowned academic had mastered the written form but mistakenly presumed that the same style could be used at a podium in the context of an hour-long public address. He treated the audience to exceptional content that was almost impossible to follow — monotone, flat, read from a script, and delivered from behind a tall podium.

He would have done well to heed the words of communication professor Bob Frank: “A speech is not an essay on its hind legs.” There is a huge difference between crafting a speech and writing an essay. And for those new to public speaking, the tendency to mimic the forms of writing we already know can be crippling.

Speeches require you to simplify. The average adult reads 300 words per minute, but people can only follow speech closely at around 150-160 words per minute. Similarly, studies have shown auditory memory is typically inferior to visual memory, and while most of us can read for hours, our ability to focus on a speech is more constrained. It’s important, then, to write brief and clear speeches. Ten minutes of speaking is only about 1,300 words (you can use this calculator), and while written texts — which can be reviewed, reread, and reexamined — can be subtle and nuanced, spoken word must be followed in the moment and must be appropriately short, sweet, and to the point.

As you focus on brevity and clarity in a speech, it’s also important to signpost and review. In a written essay, readers can revisit confusing passages or missed points. Once you lose someone in a speech, she may be lost for good. In your introduction, state your thesis and then lay out the structure of your speech ahead of time (e.g., “we’ll see this in three ways: x, y, and z”). Then, as you work through your speech, open each new point with a signpost to let your listeners know where you are with words such as, “to begin,” “secondly,” and “finally,” and close each point with a similar, review-oriented signpost (e.g., “so we see, the first element of success is x”). This lack of subtlety can be repetitive and inelegant in a written document, but it is essential to the spoken word.

Similarly, the subtleties of complex argumentation and statistical analysis can be compelling in an essay, but in a speech it’s important to drop the statistics and tell a story. Neuroscience has shown that the human brain was wired for narrative. And while I always appreciate arguments that are fact-based and grounded in sound logic, it’s easier for me to engage with a speaker when she keeps the statistics to a minimum and opts for longer and more vivid stories. Lead or end an argument with statistics. But never fall into reciting strings of numbers or citations. Your audience will better follow, remember, and internalize stories.

To bring these stories to life, remember that when delivering a speech you are your punctuation. When you’re speaking, your audience doesn’t have the benefit of visual signifiers of emphasis, change in pace, or transition — commas, semicolons, dashes, and exclamation points. They can’t see question marks or paragraph breaks. Instead, your voice, your hand gestures, your pace, and even where and how you’re standing on stage give the speech texture and range. Vary your excitement, tone, and volume for emphasis. Use hand gestures consciously and in accordance with the points you’re trying to make. Walk between main points while delivering the speech — literally transitioning your physical position in the room to signify a new part of the argument. Standing motionless while speaking in a monotone voice doesn’t simply drain your audience’s energy, it deprives them of understanding — like writing a text in one run-on sentence with no punctuation or breaks. Resist the urge to read your speech directly from the page. Become the punctuation your audience craves.

Speeches and essays are of the same genus, but not the same species. Each necessitates its own craft and structure. If you’re a great writer, don’t assume it will translate immediately to the spoken word. A speech is not an essay on its hind legs, and great speech writers and public speakers adapt accordingly.